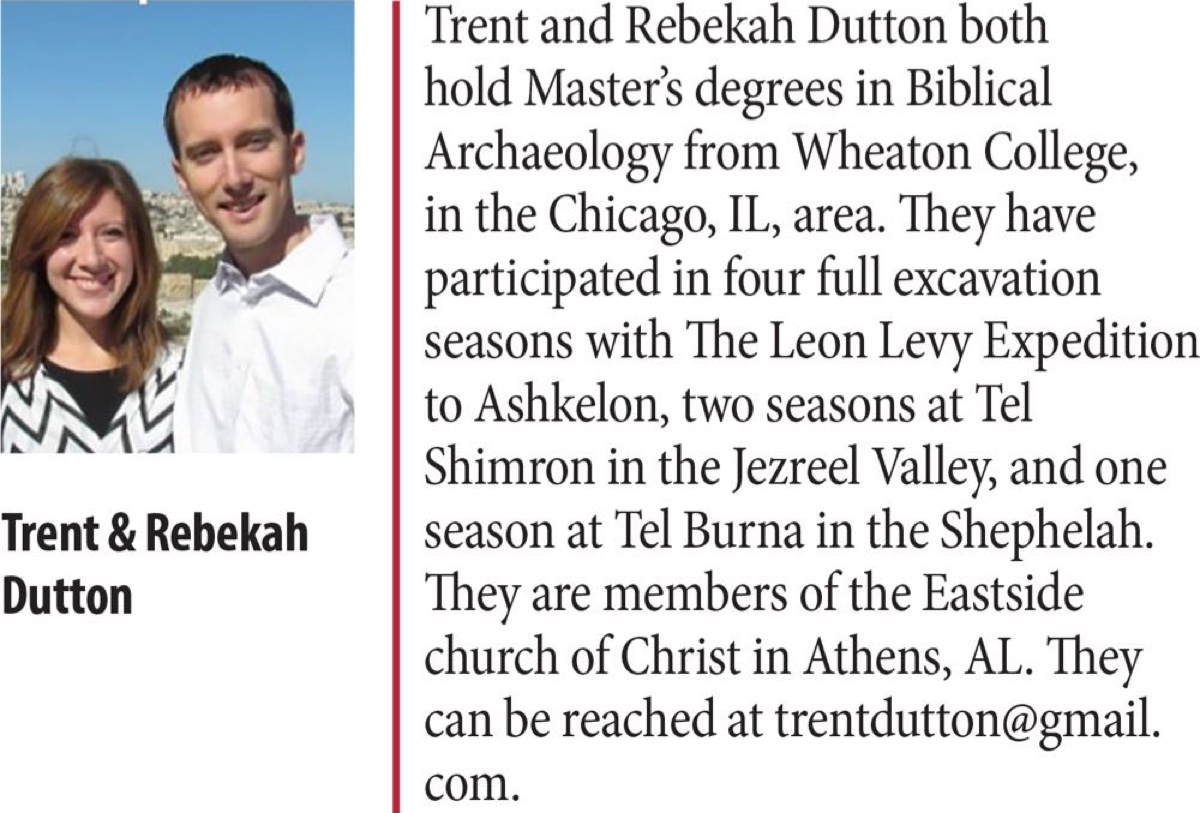

By Trent and Rebekah Dutton

Synopsis: How to approach archaeological “knowns” and a few attributes about Judean Pillar Figurines.

In our last article, we introduced Judean Pillar Figurines (JPFs). This article focuses on a few attributes we know about JPFs and how to approach what can be known.

In the context of Biblical Archaeology, how one determines what is “known” about an object is of critical importance. The discipline of Biblical Archaeology intersects with theology or exegesis, but is separate from these branches of research. One can study theology and texts (exegesis) such as the Old and New Testaments and be greatly informed by what archaeology can bring to the table. However, the methods and skill sets used to evaluate archaeological artifacts are different from theological and exegetical approaches. Archaeology is a science and very much data driven. Archaeology is excavating an area of the ground, photographing objects, testing for material composition, translating textual artifacts, and, from these actions, producing a data set for analysis. In contrast, the study of theology, hopefully in a systematic fashion, seeks to explain in an organized manner how one arrives at what he believes about God, for which there is no quantitative data. Then, with exegesis, the desire is to discover the original and intended meaning of Scripture via human logic and knowledge of linguistics. In the disciplines of theology and exegesis, there is much analyzing of concepts, ideas, and texts, but ultimately, decisions are based on interpretations of evidence. Can an individual or group operate in all three disciplines? Sure, and it is sometimes necessary. The key here is for those who are participating to be aware of where their specialties lie. For those consuming the information produced by the “professionals,” the concept is similar. One may not know the detailed methodologies for any of these disciplines, but through common sense and logic, one can seek to understand the concept of discipline specialty, limitations, and crossover when approaching these topics.

With that seemingly expansive caveat, what are some things we know about JPFs?

What are JPFs made of? Locally sourced earthen clays. This is one of the first and most simple questions to ask about an object. When identifying and classifying objects used in ritual cultic contexts, source material is sometimes very telling. For example, if an archaeologist excavates a temple site and finds a figurine made with materials not from the surrounding vicinity, that is a potential indicator of nonlocal influence. If similar finds are made at other temple sites in the region, that can begin to establish a pattern. If no related inscriptions are found and no figurines are stamped or inscribed, there is likely not enough data to ascribe an identity to the influencer. However, you have enough data points to begin asking (but not answering) a question about influence from outside the area. Could it be the religious influence of a nation state that invaded and conquered the area? Possibly. It could also be a grab bag deal of figurines a local priest picked up while traveling out of the region. These are two very different endpoints requiring much more data to answer that hypothetical question. For JPFs, they were made near where they were recovered.

From what time period do they come? The majority of JPFs date roughly from the eighth to sixth centuries BC, so think 800-586 BC, during the time of Israel’s Divided Kingdom. In the archaeological literature, you will also see this referred to as the Iron Age II BC periods. Within this three-century time period, the stratigraphy is often difficult to reconstruct. For some figurines, this is due to primitive excavation methods or record keeping from decades ago; for others, more modern excavations provided better stratigraphic control, but the actual excavated loci are often mixed or redepositions (Shiloh, 104). Additionally, these figurines do not have “typologies” that would allow researchers to establish a chronology of their development over time.

Where are they found? One of the most well-known researchers of JPFs summarized numbers in approximately forty notable sites of JPF finds (Kletter, 47). The most occurrences are in Jerusalem and one site just outside the city. One interesting note on location is that approximately 30 of those sites are within the environs of Judah, including Lachish, Beer Sheba, and Arad. Here, we do have an interesting locational pattern in that greater numbers are found in Judah and notably less in the kingdom of Israel proper. With just these numbers, one could not make definitive claims about these concentrations, but it adds data to the equation to help in determining what it could mean.

From this data, researchers can only draw limited conclusions, and only hypothesize about the larger story. We know they were made by locals using the materials at hand during the Divided Kingdom, and largely within Judah. This time period overlaps with biblical texts rebuking God’s people for their idolatry, especially with the goddess Asherah. With this timeframe and these locations, it does make JPFs legitimate candidates for being representations of Asherah as mentioned in the Old Testament. However, that can only be a hypothesis in a sea of other logical explanations of their identity and purpose.

With the topic of JPFs so much more could be said and explored, but for this brief article, there are three basic attributes that serve as prime examples of what we know from an archaeological perspective and allow researchers to form hypotheses concerning the identity and use of JPFs. Can this information inform those other disciplines? Sure—without question. Do they completely answer questions in those other disciplines? Usually not, but it does happen. Perhaps someday, a volunteer excavator will pull a JPF out of the ground that says, “This is Asherah,” and all of our questions will be answered.

Kletter, Raz. “Pots and Polities: Material Remains of Late Iron Age Judah in Relation to Its Political Borders.” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, No. 314 (May 1, 1999): 19-54.

Shiloh, Yigal, Donald T. Ariel, Alon. De-Groot, and Hannah. Bernick-Greenberg. Excavations at the City of David. Jerusalem: Institute of Archaeology, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 1984.

Image-1 Caption: Molded Head Judean Pillar Figurine. Judean pillar-based figurine from Beth Shemesh Iron II 800-586 BCE. Located in the Penn Museum 02.jpg—Wikimedia Commons

Image-3 Caption: Pinched Head Judean Pillar Figurine. Judaean female figurines—Located in the Israel Museum, Jerusalem—Wikimedia Commons