By Luke Chandler

Synopsis: New discoveries at a distant desert mine in southern Israel may answer questions involving David’s kingdom and even how the Hebrews first settled Canaan.

One controversy with archaeology and the Bible involves the early monarchies of Israel and Judah. The Bible describes active, powerful leaders such as David and Solomon, but archaeology finds little physical evidence of their kingdoms. This gap leads some to doubt their historical existence.

Likewise, the Hebrews’ entry into Canaan brings an archaeological puzzle. The Bible puts Israel’s entrance into Canaan around 1400 BC, but new farming villages, reflecting a new population, don’t appear until one and a half centuries later. This contrast leads some to distrust the Bible’s historicity.

An archaeologist named Erez Ben-Yosef may help untangle these controversies. He has been excavating ancient copper mines at Timna, a remote desert site far south of the Dead Sea. Copper was once in high demand as a key ingredient in bronze, a strategic metal for ancient peoples. Ben-Yosef has demonstrated the Timna copper mines were most active during the tenth and nineth centuries BC, the time of David, Solomon, and other early Hebrew kings.

Why does dating mine operations to the early kings matter? High demand for bronze would come from powerful nations for production of weapons and tools, and for use in monumental architecture. Skeptics have dismissed the existence of the early kingdoms, insisting societies of the tenth and nineth centuries were still tribal, yet Timna’s massive level of copper production suggests otherwise.

Recent information from the Timna mines now reveals a different picture of tenth—nineth century Canaan than many have believed. Rather than a tribal backwater, the area was commercially active with organized societies, even if not strongly urbanized.

The Timna mines required thousands of people to sustain their production of copper, even with the region’s intense heat, less than one inch of annual rainfall, and no arable land. Food and water for all workers, guards, and support staff had to be brought in from afar. The hundreds of pack animals needed for this also consumed huge amounts of water and fodder. Workers also needed imported materials for mining and smelting, such as charcoal, clay, flux, ground stones, and large quantities of tools. Traces of a security network for the supply chain, such as manned forts and observation posts, have also been found. These complex and expensive logistical operations over long distances reflect a strong society able to command and control a wide area.

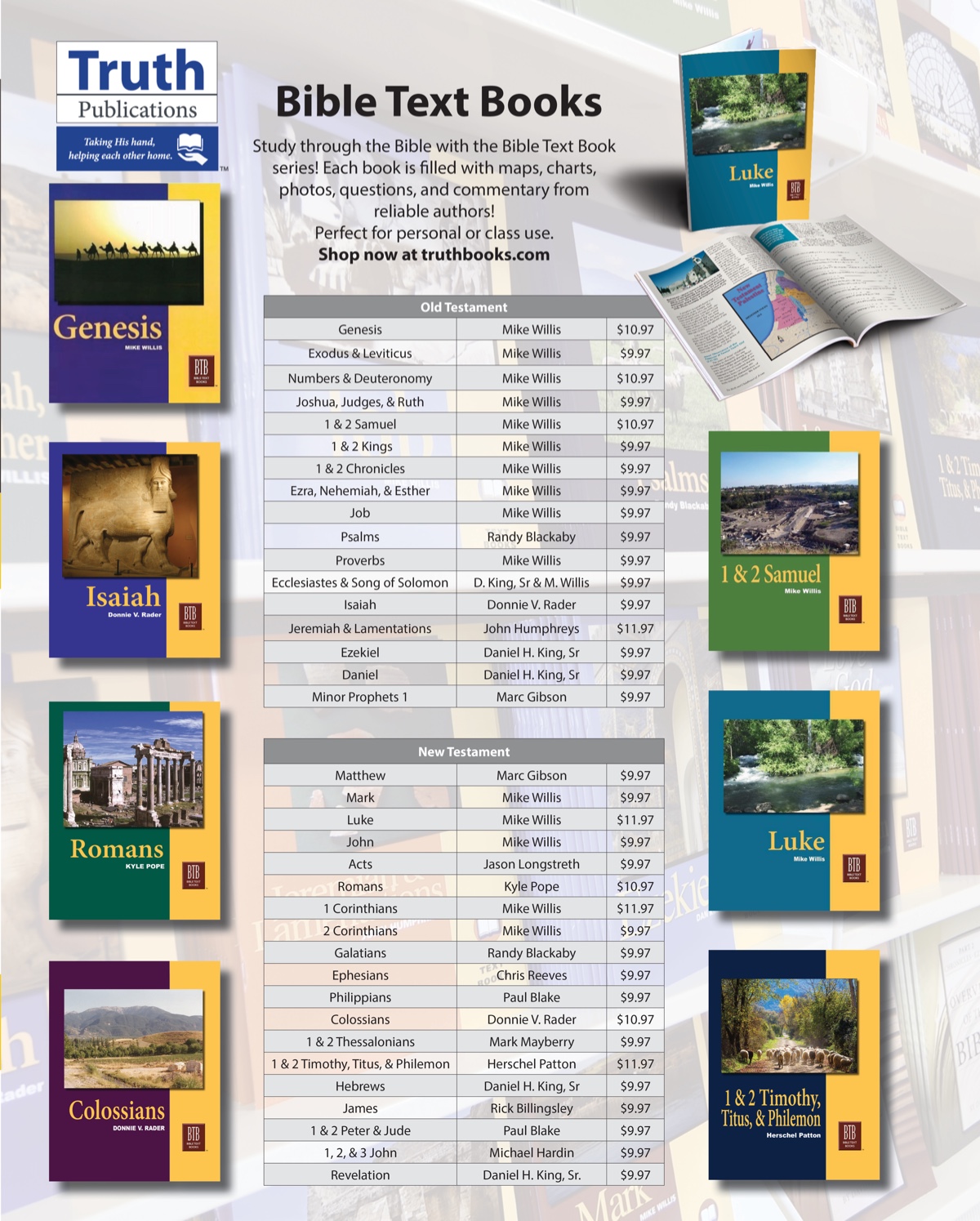

The Timna excavations also discovered evidence of an elite upper class that oversaw operations. Luxury products found at Timna include dyed fabrics (with the costly royal purple), premium cuts of meat, dried fish from the Mediterranean Sea (185 miles distant!), along with figs, pomegranates, and olives. These items point to a developed commercial society existing in the middle of a harsh desert.

Who was running these massive copper mines, with a splendid supply chain, in the time of David and Solomon? Ben-Yosef attributes the mine operation to Edom, which is remarkable since the Edomites were nomadic in the tenth and nineth centuries. They were not living in cities or erecting large stone buildings. They lived in tents, yet successfully managed a highly complex mine operation and supply/commerce chain.

Archaeologists do not consider nomads capable of functioning on a high societal or political level. Developed societies are normally linked with physical structures. Ben-Yosef now describes this presumption as “architectural bias.” Timna shows nomads could exist and compete on the level of an urbanized society. The Edomites of the tenth century BC managed complex economic connections and demonstrated controlling power over a large region.

This new understanding of Edom gives us a fresh perspective on David’s kingdom, and even Israel’s first generations in Canaan. Nomads tend to be archaeologically invisible and easy to miss—or at least misunderstood. Did the kingdom of David need many physical structures to be powerful, organized, and control its space? Did the Hebrews immediately build houses when they settled in Canaan or did they continue as nomads for a time, transitioning to settled farming generations later? Can an “architectural bias” lead archaeologists astray?

Timna makes us rethink how to define an organized society. It also reminds us that, when we perceive a conflict between the Bible and archaeology, the error is often in us; we wrongly interpret one or the other—or even both. We find wisdom through care and humility with Scripture, and also with its archeology.

Image-1 Caption: A fabric dyed with the costly Royal Purple. This and other luxury goods reveal a sophisticated commercial network and supply chain operating in this remote desert region of Timna.

Credit: Dafna Gazit—Israel Antiquities Authority.

Image-2 Caption: “A view of Tinma. Ancient copper mines in this desert region may help to resolve some perceived conflicts between the Bible and archaeological finds.”

Credit: By Eliran T—Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0 File: Timna Valley Panoramic.jpg—Wikimedia Commons

Image-3 Caption: Bedouin Tent