By Trent and Rebekah Dutton

Synopsis: In this article, we offer an introduction to these artifacts from the period of Israel and Judah’s divided monarchy.

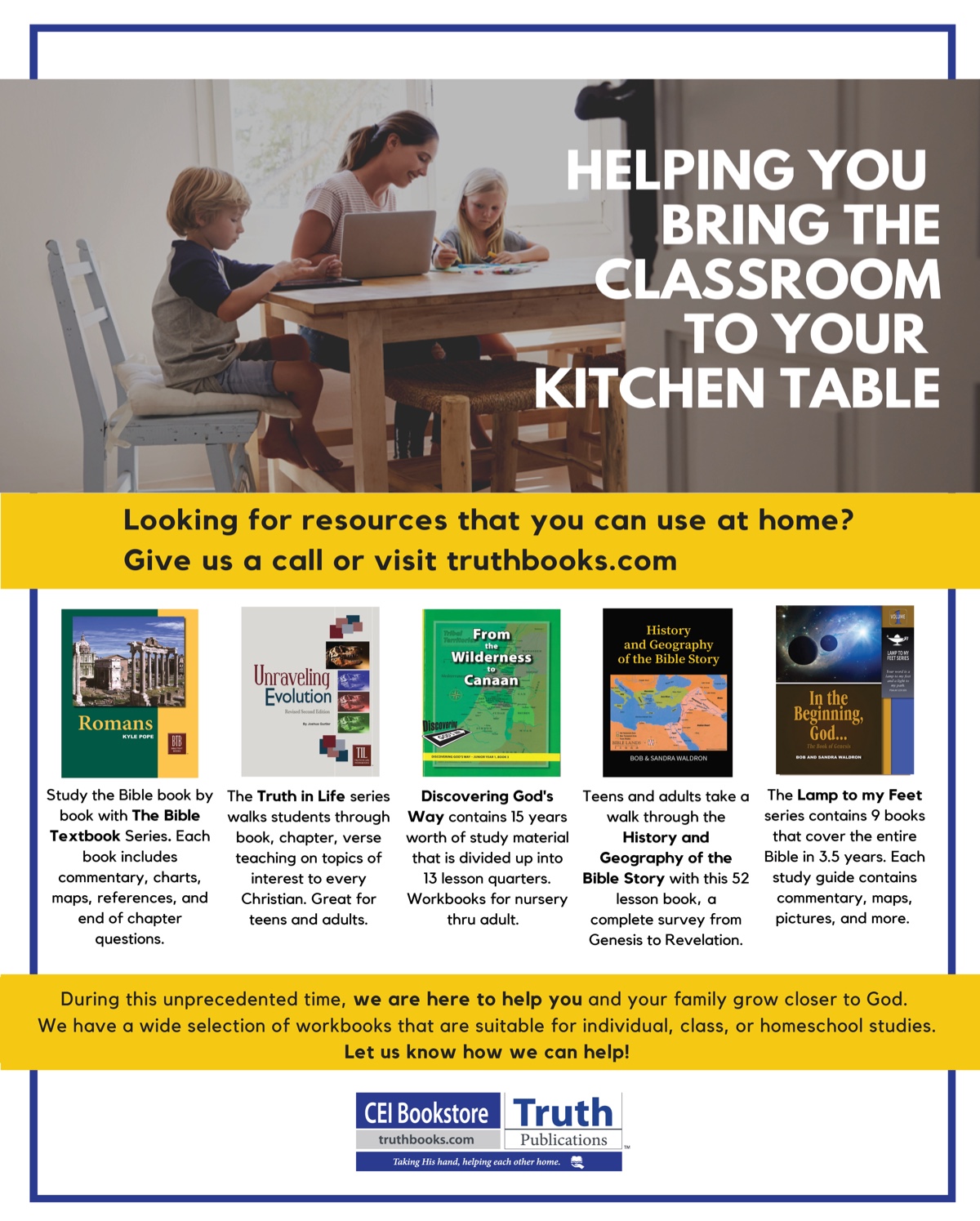

In the coming months, we will have a few articles to introduce and discuss Judean Pillar Figurines (JPFs). These objects are small, terra-cotta (unglazed earthenware clay) figurines that depict a female form in the upper half of the figurine, while the lower half has no human form, but rather a “pillar base” shape. The base allows these figurines to stand on their own. Over 1000 of these figurines have been found in the Judean region of Iron Age II Israel. Most figurines in that time period date to the seventh and eighth centuries BC, correlating with Israel and Judah’s divided monarchy period. While roughly half of the figurines known today have been found in Jerusalem (approx. 400), the rest have been unearthed at sites scattered throughout the region of Judah, with a few found outside of the area.

In decades past, these figurines had been thought of as fertility objects, but this assertion has been debated over the years. More nuanced classifications have been suggested by recent scholarship. Because of time frame and geographical proximity, JPFs have long been associated with the Iron Age Western Semitic goddess Asherah, who is frequently mentioned in the biblical text. Other suggestions for form and function of the JPFs range from votive representations to simple toys. Whatever their representation and function, JPFs are so numerous and found in such varied contexts, it suggests commoners and elites both possessed these small items. While the debate continues, more recent research examines explanations for the abundance of these figurines in times of declining power in Israel, such as a culture seeking to define and retain an ethnic identity in the face of Assyrian imperialism.

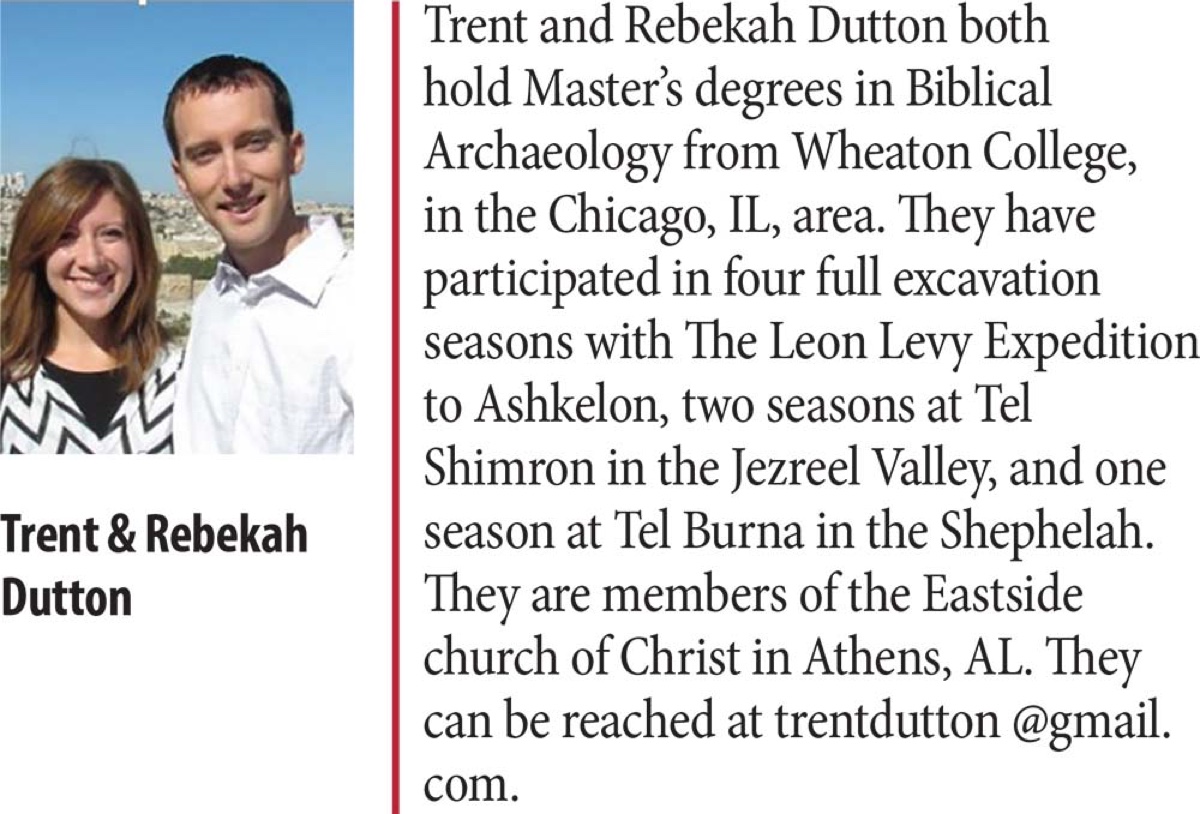

There are two major styles of JPFs. One is a “pinched” head style, and the other is a “molded” head style. These two styles usually have similar bases. With these different styles, patterns seem to emerge, particularly in Jerusalem, as to which was more popular. Numbers from both Shiloh’s (an archaeologist, not the location) and Kenyon’s excavations in Jerusalem show a general rise in popularity over time of the pinched heads over the molded heads. Later excavations in Jerusalem and other surrounding areas show that this trend continues. This observation will come into play in later articles, but for now, the point here is to note the differentiation of styles.

Another note on these artifacts is location. With a few noted exceptions, the JPF dataset almost entirely resides in the environs of Judah and not Israel. The greater concentration is certainly around Jerusalem, but other regions and cities around Judah, such as in the Shephelah (Lachish) and the Negev (Beer Sheba and Arad), also have decent numbers of these artifacts.

So, what about the questions already posed, and others, for these artifacts? Are they idols? Do they represent the Asherah? Why are so many in Judah? Is there any meaning or distinction between the pinched heads variety versus the molded ones? Are these artifacts and any of these associated questions useful in reading the Biblical text? There are several questions that can go wide and deep, but we will try to offer a few useful observations in the articles to come. Other installments will discuss lessons that can be deduced from the objects, some things the objects do not tell us, and then how they compare with other artifacts from the same time period and cultural environment.

One challenge with a topic like this is the traditional and low context use in theological applications. For example, scholarship from decades ago with names such as Dever (in the 1970s and 2000s) and Kletter (mid-1990s), both attribute JPFs as being Asherah and/or other goddesses. This research has been available for years and permeates blog posts, books, and sermons or popular writings. How this is usually presented to the layperson audience is by a quick image flashed on the screen and explanation that JPFs equal Asherah. Is this true? Maybe. It is certainly a possibility for many of the ancient people who would have held these objects. However, these artifacts existed over a span of a few hundred years over a changing political and religious landscape. A more likely scenario is that, while commonalities may have followed the objects in purpose and meaning, they likely meant different things to individuals and were used in different ways over time. More recent scholarly research reflects nuances such as this being possible. Darby notes that their function may have been apotropaic, semi-religious, and iconographic in a way that the users may not have even fully grasped.

In the end, it may seem that approaching and trying to understand artifacts like the JPFs is fraught with pitfalls and rabbit holes from which one may never return. Those hazards exist, but with a specialty discipline such as this that intersects with the Biblical text, value exists in trying to understand these objects that ancient people were holding. When we look at a passage that mentions Asherah, or read of an idol crafted from leftover wood (cf. Isa. 44), there is no guesswork regarding how God felt about these idol images. However, what did these images look like? Do we have examples of them? These curiosity questions cannot help but come to the surface when artifacts like JPFs come out of the ground. With that, it is worth examining the objects to understand what they can tell us, and often more importantly, what they cannot tell us.

Darby, Erin Danielle. Interpreting Judean Pillar Figurines: Gender and Empire in Judean Apotropaic Ritual, 2011. https://dukespace.lib.duke.edu/dspace/handle/10161/5661.

Wilson, Ian Douglas. “Judean Pillar Figurines and Ethnic Identity in the Shadow of Assyria.” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 36, no. 3 (February 28, 2012): 259-78. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309089212438002.

Image-1 Caption: Molded Head Judean Pillar Figurine. Ceramic Judean pillar-based figurine Beth Shemesh Iron II 800-586 BCE Penn Museum 02

[https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ceramic_Judean_pillar-based_figurine_Beth_Shemesh_Iron_II_800-586_BCE_Penn_Museum_02.jpg]

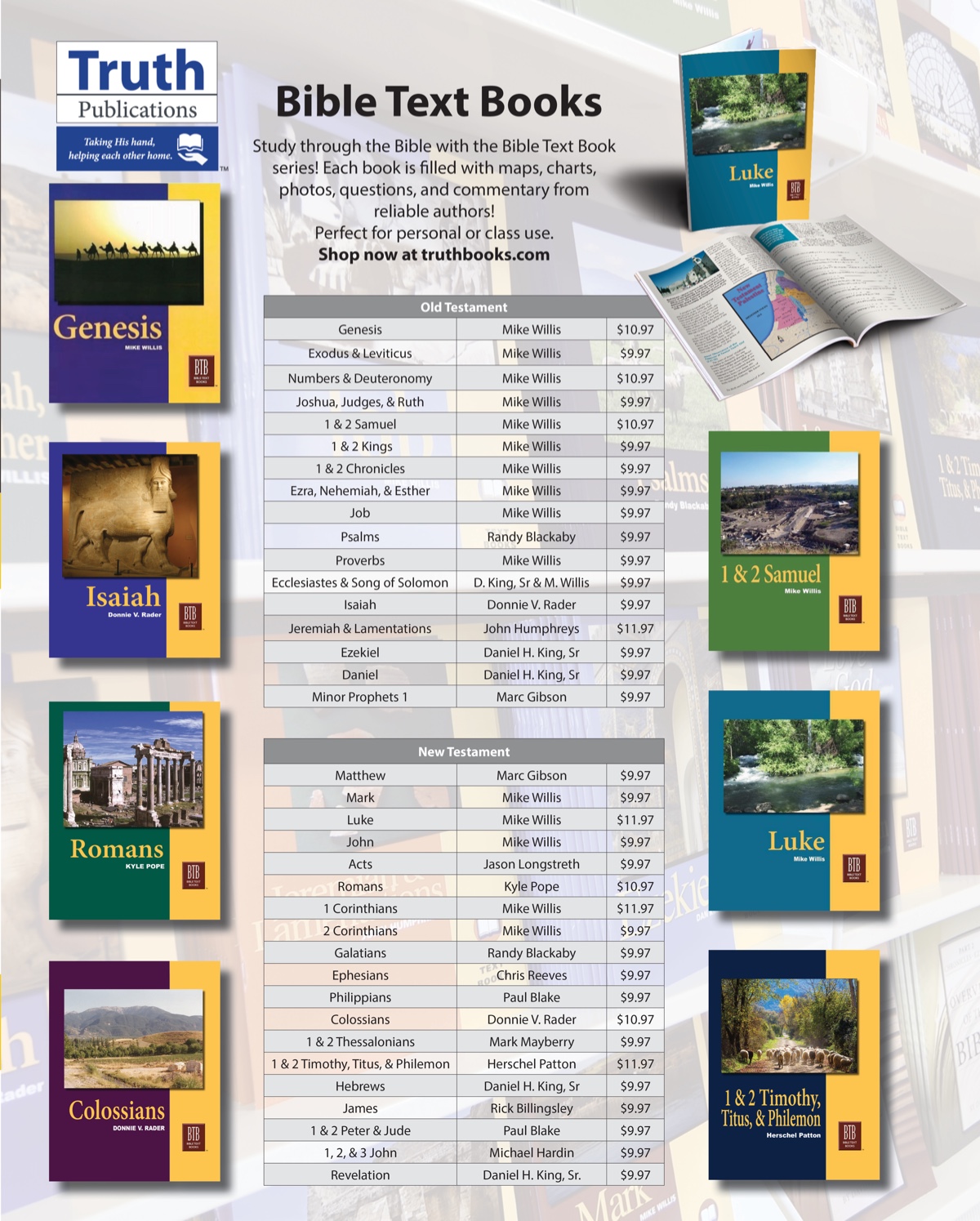

Image-2 Caption: Molded Head Tel Berna 2019

This photo is from Rebekah’s 2019 dig at Tel Burna © Trent and Rebekah Dutton.

Image-3 Caption: Pinched Head Judean Pillar Figurine.

[https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Judaean_female_figurines_-_Israel_Museum,_Jerusalem.jpg]