by Steve Wolfgang

Synopsis: For Christians, one of the most important elements in their worldview is the evidence of God in nature and in history, including the Bible.

“The past is a foreign country—they do things differently there.”1

Since “history” means many things to various people, definitions are obligatory. Basic meanings include: (1) Whatever actually occurred; (2) material evidence from that time—physical artifacts, inscriptions, and documents such as letters, interviews, after-action reports, “official” chronicles, eyewitness memoirs, etc. (3) those records that have survived to be used by historians2—often referred to as “primary sources,” and (4) “secondary” accounts produced by historians using many of the above resources—that is, how historians choose to tell stories of the past, writing from various perspectives and selecting portions of the available evidence to privilege as sources.

Historical knowledge is never exhaustive, uncorrectable or absolute. 1 Corinthians 13 isn’t speaking specifically about history, but the words apply nonetheless: “We know in part. . . [as] in a mirror dimly.” Still, history is arguably the broadest of subjects, since one can write a history of nearly anything. Even so-called “prehistoric” eras have produced evidence, albeit non-documentary, used by scientists to imagine or conjecture about their historical meaning.3

History is about far more than merely learning facts, biographies, and timelines. It also can teach how to think analytically, argue logically, and communicate persuasively. Each generation asks new questions and consults previously-unused evidence—especially as historians’ ranks are increased by women and minorities.4 Even Biblical writers chose selective information to tell the story they recorded (John 21:25).

For Christians, one of the most important elements in their worldview is the evidence of God both in nature and the human past. Indeed, “All history. . . must be held by Christians to be a story with a divine plot.”5 In contrast to a cyclical view of history, widespread in ancient and oriental civilizations, where events regularly recur as with seasonal patterns of nature, Christians see this “plot” through a linear view of history as a process moving towards a climax determined by God.6

The most obvious place to look for God in history is, of course, the Bible. God is revealed as the Creator of life in all its diversity. Paul taught Athenians that “the God who made the world and everything in it, being Lord of heaven and earth. . . made from one man every nation of mankind to live on all the face of the earth, having determined allotted periods and the boundaries of their dwelling place” (Acts 17:24, 26, ESV).

In the Old Testament, God acts in historical events, displaying his power in the Exodus and other events (Ps. 136 and other “historical” Psalms). God cares about human events and interacts on the world stage, raising up and casting down kings (Exod. 15:1-4ff; Dan. 2:21). Biblical events intersect those of world empires, such as Egypt, Assyria, Babylon, Persia, Greece, Rome, etc. Records and artifacts of those empires often correlate and illuminate what is recorded in Scripture, rather than, as many suppose, being merely mythological or fictional.7

The Bible not only describes God’s actions in ancient history, but explains why such things happened. Common events which might easily be interpreted as natural phenomena (for instance, the frequent occurrence of locust plagues in the Ancient Near East), are instead identified in Joel’s case as God’s “army” (2:11-14). The collapse and captivity of the Israelite nation are explained by the biblical historian not simply as the frequent rise and fall of empires; rather, “this occurred because” of Israel’s spiritual decadence and disobedience (2 Kings 17:7).8

Without doubt, God is sovereign and still operates in human affairs, though, like much of history, determining divine intervention from natural phenomena (or God’s use of such events) is not always knowable. Fallen humans have a seemingly limitless capacity for misinterpreting events—and even God’s revelation—thus contemporary occurrences have become fodder for uninspired and misguided authors to see “the hand of God” where it is not. God has been blamed falsely for hurricanes, epidemics, and various social upheavals. As one historian observes, “God has been on every side of every social issue I have ever studied; He has participated in every war on every side; He is a Democrat and a Republican, high tariff and low tariff, a fascist and a communist.”9 God has His own purposes, which are not always plain to mortals.

God’s decisive actions culminated in the life, teaching, and victorious resurrection of Jesus, and His eternal purpose continues to unfold through Christ’s church and the promise that history will end with Jesus’s return in judgment. From the beginning, God’s intervention in history, often in judgment or mercy, points to His triumphant conclusion of history: “Jesus wins” in the cosmic struggle between good and evil!

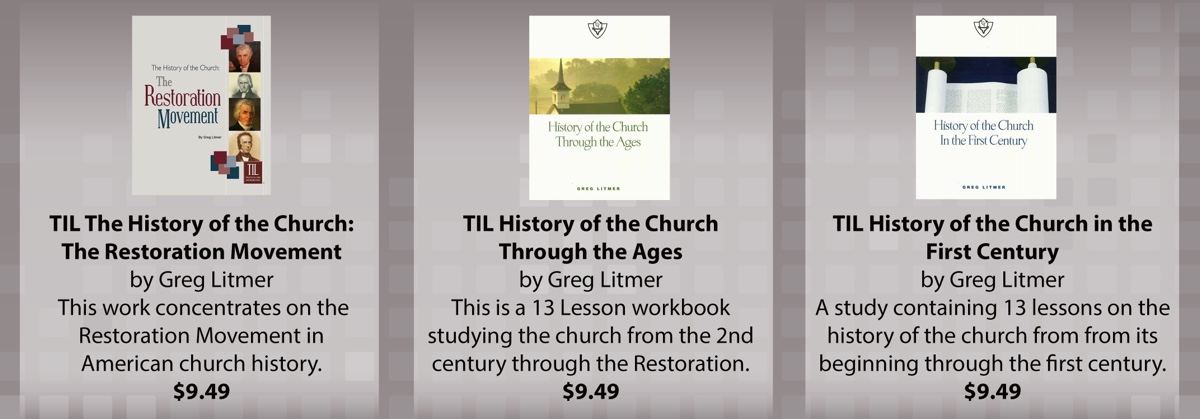

Resources in the notes, and other material, may be ordered from Truth Publications.

David Lowenthal, The Past Is a Foreign Country (Cambridge University Press, 1985).↩︎

One typical example: of millions of pay vouchers issued to the Roman legions over several centuries, only six and a fragment of seventh are known to survive. See Steve Wolfgang, “Mesopotamia,” In the Beginning: Studies in Genesis (Truth Publications, 2018), 179-180, citing Edwin Yamauchi, Stones and Scriptures (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1972), 146ff.↩︎

Stephen J. Gould explains: “As a paleontologist and evolutionary biologist, my trade is the reconstruction of history. History is unique and complex. It cannot be reproduced in a flask. Scientists who study history, particularly an ancient and unobservable history not recorded in human or geological chronicles, must use inferential rather than experimental methods.” The Panda’s Thumb: More Reflections in Natural History (New York: Norton, 1988), 27-28.↩︎

Mark Noll clarifies: “Historians must select what to include and not to include [and] decide how to slant what is written, and they must highlight certain themes at the expense of others [including] the experiences of women, nonwhites, and ‘ordinary’ people who did not leave extensive written records.” A History of Christianity in the United States and Canada, (Eerdmans, 2019), 1.↩︎

C.S. Lewis, The Discarded Image: An Introduction to Medieval and Renaissance Literature (Cambridge University Press, 1964), p. 69, Kindle Edition.↩︎

John Warwick Montgomery’s volumes on such matters were helpful to me as a young history graduate student. Begin with Where Is History Going? A Christian Response to Secular Philosophies of History (Zondervan, 1969).↩︎

James Hoffmeier and Dennis Magary, Do Historical Matters Matter to Faith? A Critical Appraisal of Modern and Postmodern Approaches to Scripture (Crossway, 2012); and Kenneth A. Kitchen, On the Reliability of the Old Testament (Eerdmans, 2003).↩︎

One excellent curriculum, incorporating rather than ignoring Biblical events in the timeline of history, used in home-school programs such as Classical Conversations, is Susan Wise Bauer’s Story of the World, based on adult texts such as her History of the Ancient World (Norton, 2007).↩︎

Ed Harrell, “Peculiar People: Rationale for Modern Conservative Disciples,” in Disciples and the Church Universal (Nashville: DCHS, 1967), 43. Harrell, Gaustad, Boles, et. al. Unto A Good Land (Eerdmans, 2005) skillfully integrates often-ignored religious matters into the broader tapestry of history, as does Thomas Kidd’s textbook, American History (Nashville: B&H Academic, 2019).↩︎