by Kyle Pope

Synopsis: In article four, Kyle asks if conclusions interpreting these issues as expedients are consistent in light of conclusions we draw on other issues.

Brother Burleson is correct that we are in agreement on most things. That is exactly why I believe discussions like this are important if we are to be united "in the same mind and in the same judgment" (1 Cor. 1:10, NKJV). Some brethren, over the years, have argued that viewing biblical silence as prohibitive, or looking to what Scripture says, shows, or implies1 for biblical authority are modern inventions, unknown in the first century. I was pleased to learn in 2017, that Doug does not believe that. He affirmed confidence in the prohibitive nature of biblical silence (58-66) and wrote, "All of Scripture must be read in the context of commands, examples, and inferences being made as a result of God's gracious pursuit of an erring people whom He desires to save (1 Tim. 2:4)" (70).2 In these points we fully agree.

I ask, however, is it not making the same faulty argument from the past to argue that distinctions between individual and congregational responsibilities are "post-Enlightenment" thinking contrary to a "group-oriented Greco-Roman" mindset? Let's test that. In addressing 1 Timothy 5, Doug acknowledged that, "there are responsibilities given to families if certain criteria apply and other responsibilities given to congregations . . . if different conditions exist." Is that a "false dichotomy"? Doesn't that show distinctions between collective and individual (or at least family) responsibilities are not a modern construct, but biblical principles?

In the issue of collective benevolence to non-Christians, brother Burleson has essentially argued that if God can do good to "the just and the unjust" (Matt. 5:45), God's actions grant authority for what the church does collectively. Certainly, we are to be "imitators of God" (Eph. 5:1), but how far can we take that? God can make laws—can the church? No, "there is One Lawgiver" (Jas. 4:12). God can carry out capital punishment (cf. Acts 5:1-10)—can the church? No, withdrawal of social contact is the only punishment authorized for the church (cf. 2 Thess. 3:6, 14; 2 Cor. 2:6).3 Obviously, there are limits to the sense in which we imitate God. So clearly, not all of God's actions are generic authority for what the church does collectively.

Our task in this discussion is to determine if these issues are generically authorized and may thus be considered expedients, or if they are additions for which the Scriptures grant no authorization. Brother Burleson has made the case that the example of God and instructions like Galatians 6:10 authorize the church collectively to offer benevolence to non-Christians. Our friends who believe in the use of mechanical instruments of music make a similar case. They assert, "If instruments are used in heaven we can use them in the assembly." Or, "Since we are told to praise God, instruments are an expedient to do that." Now brother Burleson and I both reject those conclusions, but why? In part, because we both believe that approved examples are binding. There is no example of collective worship to God on earth with a mechanical instrument in the NT. If this conclusion is valid, the same principle must determine our views on these issues. If there is no approved example of collective benevolence to non-Christians (or support of human institutions) in the NT, the same approach to biblical authority that leads us to mutually reject the instrument should lead us in unity to mutually rejecting these practices as additions, not expedients.

To attain this unity, I must convince Doug that there are no such examples. He has appealed to 2 Corinthians 9:12-13 as an example of collective support for non-Christians. For this to be true we would have to understand the phrase "needs of the saints" to stand in contrast to needs of non-saints, but that's not what it says. The Corinthians' help supplied the saints "needs," Gr.hustrēma"deficiency, that which is lacking" (Thayer), "but also" was "abounding through many thanksgivings to God" (2 Cor. 9:12b). The contrast is between needs that were lacking, and thankfulness that was "abounding"—not different recipients of the giving. The word translated "sharing" (NKJV, NIV), "contribution" (NASB, ASV, ESV), or "distribution" (KJV), also helps us understand the scope of this gift. It is the familiar word koinōnia—usually translated "fellowship" (YLT, GLT). In the previous chapter, Paul described the same gift as the "the fellowship (koinōnia) of the ministering to the saints" (2 Cor. 8:4). Only two chapters before this Paul wrote:

Do not be unequally yoked together with unbelievers. For what fellowship (koinōnia) has righteousness with lawlessness? And what communion has light with darkness? And what accord has Christ with Belial? Or what part has a believer with an unbeliever? (2 Cor. 6:14-15).

Certainly, context determines the meaning of any word, but are we to conclude that Paul prohibits koinōnia with unbelievers, only to commend it three chapters later? Paul is reporting the results of, "the generosity of the fellowship toward them [i.e. the saints in Jerusalem] and toward all (eis pantas) [i.e. likely other saints in Judea (cf. Acts 11:29—"relief to the brethren dwelling in Judea")]" (2 Cor. 9:13, GLT). "All" is still speaking of "saints," but includes those outside of Jerusalem.

We noted in our first article the name for this first day of the week collection of the church—it is "the collection for [eis, lit. "unto"] the saints" (1 Cor. 16:1, NKJV). This is not the only time it is described that way. When Paul told the Romans about this type of gift he spoke of "going to Jerusalem to minister to the saints" (Rom. 15:25), explaining, "For it pleased those from Macedonia and Achaia to make a certain contribution (koinōnia) for the poor among the saints who are in Jerusalem" (Rom. 15:26). Does that explain what "remember the poor" actually means (Gal. 2:10)? Further, it was called "the gift and the fellowship (koinōnia) of the ministering to the saints" (2 Cor. 8:4). Paul's teaching on giving that spans 2 Corinthians 9:1-15 begins with reference to the "ministering to the saints" (2 Cor. 9:1). Does this mean nothing? If the collection is intended for broad general distribution to any poor, or to any good cause why is it said to be "for the saints"?

Let's go back to 1 Timothy 5. Unqualified widows were not to be "taken into the number" (1 Tim. 5:9) of those receiving regular support from the church. God cares for all widows (Deut. 10:17-18), but the church collectively was not to assume this work. Their family was to assume that duty (1 Tim. 5:16a), but for unqualified widows the church was not to be "burdened, that it may relieve those who are really widows" (1 Tim. 5:16b). Let's note several things about this. First, the church collectively is not responsible for some things. Second, to assume things outside of its responsibility prevents it from carrying out its work. Third, the church cannot care for all in need (John 12:8, "the poor you have with you always"), but it is capable of carrying out relief for the "needs of the saints."

In this round our discussion expands to include the topic of "institutions." Doug is right that God established the home, civil government, and the church, but this very fact demonstrates the issue at hand. Most non-institutional brethren do not oppose the existence of human institutions—any cooperative effort that isn't the home, the church, or civil government is a human institution. The issue is do the Scriptures authorize the church to operate, support, or promote any human institution—whatever its work?

I will address Doug's points in my final article, but let me end this study with some practical challenges. We stand before a denominational world challenging them to reject human additions and follow biblical patterns for church organization. Consider how entanglement with human institutions compromises that appeal. If the church is authorized to do a work, Scripture describes congregations doing that work themselves. Where is authority for accomplishing that work vicariously through a separate organization? If it is an institution comprised of people outside of a congregation can elders truly be said to "watch out for" the souls of those who are not under their oversight (Heb. 13:17)? Where is authority for such oversight to begin with? How can we call on the world to reject their unscriptural innovations while clinging to our own?

1 Brother Doy Moyer offers this powerful simplification of the terms "command, example, and necessary inference," arguing that all communication relies on these concepts (see Mind Your King: Lessons and Essays on Biblical Authority, Birmingham, AL: Moyer Press, 2016).

2 Doug Burleson, "Bible Authority," Pursuing the Pattern: A Careful Examination of New Testament Practices, Ed. Jim Deason. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2017, 55-74.

3 These examples are extreme, but there have been those in history who have presumed these works for the church. The very fact that we view them as extreme demonstrates that we recognize the limits of our imitation of God.

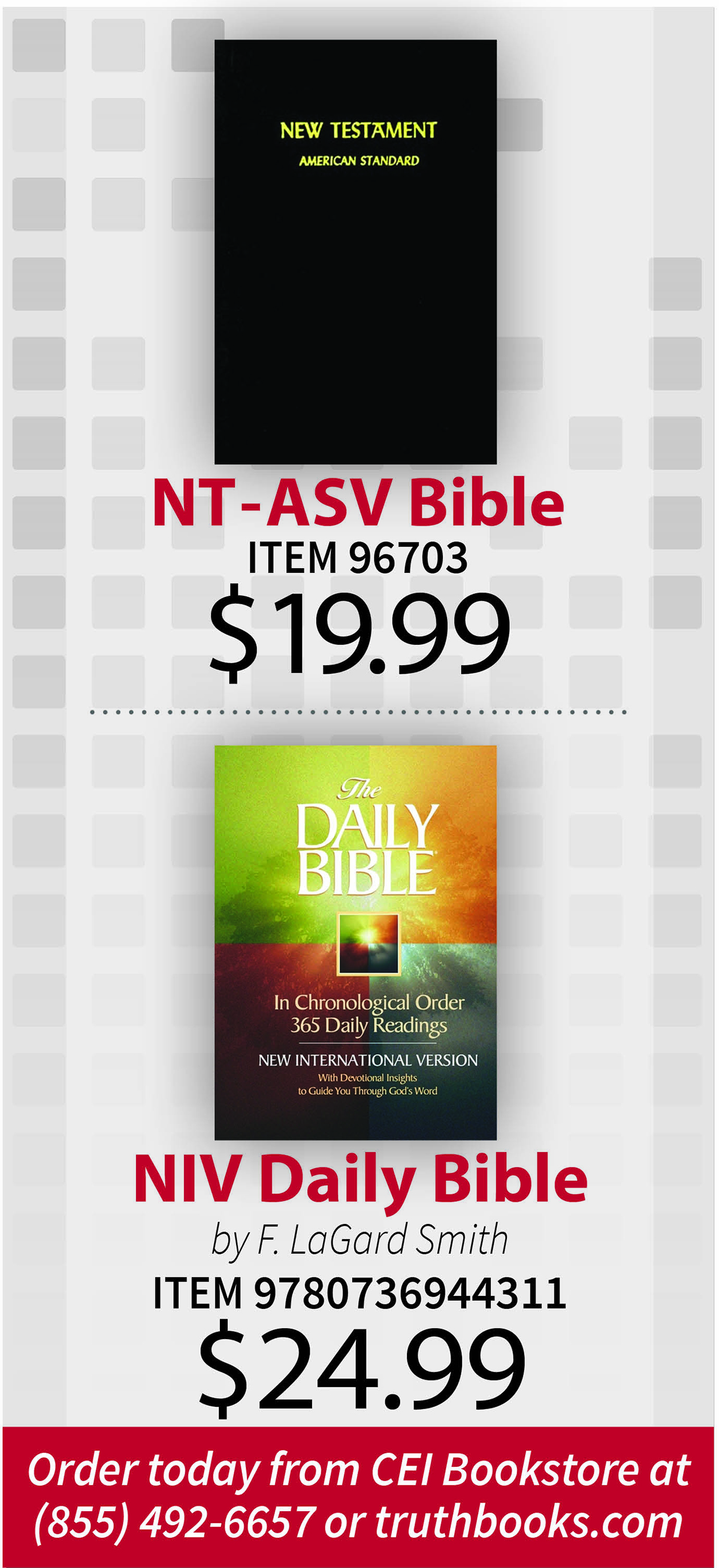

Author Bio: Kyle preaches for the Olsen Park Church of Christ in Amarillo, TX. He has written several books published by Truth Publications including How We Got the Bible. The church website is olsenpark.com. He can be reached at kmpope@att.net.