by Trent and Rebekah Dutton

Synopsis: Tel Shimron is a unique site that begins to unveil what life was like as a border city between the cosmopolitan Mediterranean and the traditional world of Galilee.

Archaeology brings the richness of the biblical narrative from the black-and-white pages of a text into vibrant, three-dimensional reality. The further value that archaeology provides is a deeper insight into the politics and culture between the lines of the inspired narrative, the daily realia of the biblical world. Sites like Tel Shimron are wholly peripheral to the Bible narrative, but this only enhances their information, being free from the distractions of theological implications or the wonder that Abraham or Ruth, or even Jesus, once stood there.

Tel Shimron is a new excavation first considered in 2013, as the Museum of the Bible sought an expedition to sponsor in partnership with Wheaton College. Tel Shimron represented the largest unexcavated site in Israel, having been briefly surveyed only in the 1980s. The initial site survey took place in 2015 and included surface surveys, where teams of archaeologists picked up and dated all the pottery they could find within thirty-by-thirty-foot squares across the site. Normal seismic activities and erosion help even deeply buried objects, like ancient pottery, to work their way to the surface over millennia. A surface survey can give researchers a reasonably accurate overview of the time periods represented at a site. This is further aided by ground-penetrating radar (GPR), which detects solid objects beneath the surface that could represent architectural features like walls. The final step is to dig test pits, which are excavations in miniature, five by five-foot squares, in areas that the pottery surveys or GPR indicate may be archaeologically "interesting." These test pits can tell us if the surveys are right.

The site itself creates a forty-eight-acre radius around a natural hill rising nearly 200 feet above the northwestern edge of the Jezreel Valley. Its earliest evidence of human presence dates to the Neolithic Period (mid-4000s BC) and is found in the basalt quarry on the southeastern edge of the tel. Basalt, a dark, volcanic stone, was coveted in the ancient world as the raw material for grinding and pounding tools like grindstones, mortars and pestles, and hammers. However, basalt was not the only stone that attracted settlers to the site. Flint was also abundant, allowing households to easily make tools, such as knives, axes, and scythes. This free supply of flint led to a preference for stone tools over expensive metal tools well into the Persian era (550-330 BC).

As the city grew in wealth and power in the region, Shimron, like other mighty Canaanite cities in the Middle Bronze Age (2000-1750 BC), built monumental fortifications to flaunt its strength. Even Shimron's wall had a uniqueness provided by its homegrown resources: rather than simple earthworks like its neighbors, it was built with a basalt asphalt core, making it nearly impenetrable for even modern tools.

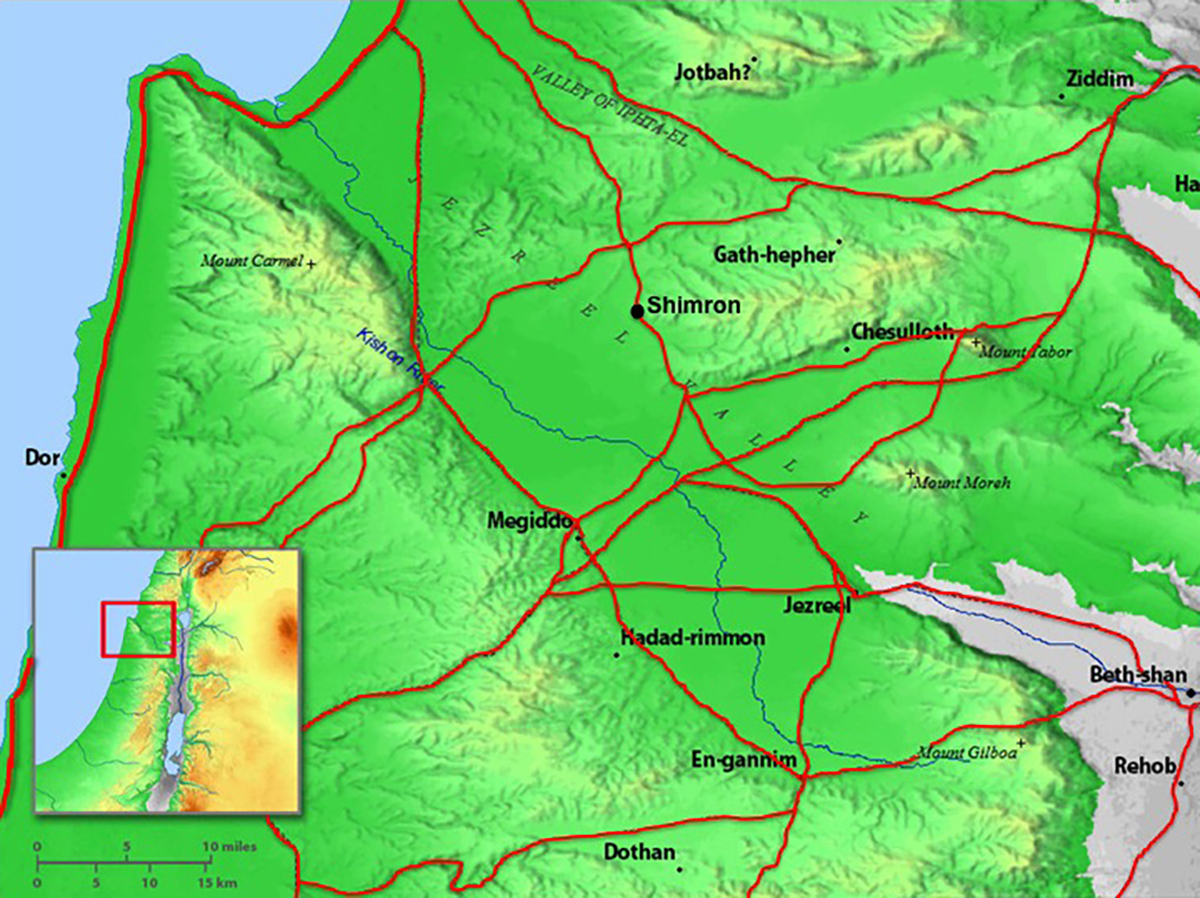

As inhabitants began establishing cities in the Jezreel Valley, they sought out positions that would give them both defensive and economic advantages. This meant founding settlements on hills that provided vantage points to watch for enemies, and also close enough to trade routes where caravans would voluntarily pause to sell their wares or could be coerced into paying tolls. The founders of Shimron landed on a goldmine, in this sense, with their hill commanding the junction between coastal highways of the south and roads stretching across the Jezreel from Acco to the Trans-Jordan.

Walled cities like Shimron did not escape unnoticed from the powers surrounding Canaan. Empires, such as Egypt, maintained footholds in distant regions by making vassals of such cities, or at least setting up administrative centers to encourage loyalty. Evidence from as early as 2040 BC demonstrates that Shimron served Egypt's interests. Even after Egypt withdrew around 1800 BC, Shimron did not stay independent but swore its allegiance to the more powerful state of Hazor. This continued until some time between 1400 and 1200 BC when the Shimron caught the attention of a new player in the region—the emerging state of Israel that incorporated it into Zebulun's territory (Josh. 11, 12, & 19). Even as it changed hands, Shimron's role in the Jezreel altered little, except that, as the Greeks and Romans influenced the land, Shimron was increasingly forced to choose between two masters: the cosmopolitan pagan world of the Mediterranean coast or the orthodox Jewish world of Galilee.

Sites like Shimron, while not playing a dominant role in the biblical narrative, still tell us much about the socio-political world surrounding the Bible, perhaps even more so than the locations of pivotal biblical events. In later articles, we will discuss how border cities like Shimron also illustrate how Israel struggled between dedication to God and the influence of their Canaanite neighbors.

Author Bio: Trent and Rebekah both hold Master's degrees in Biblical Archaeology from Wheaton College in the Chicago, IL area. They have participated in four full excavation seasons with the Leon Levy Expedition to Ashkelon, two seasons at Tel Shimron in the Jezreel Valley, and one season at Tel Burna in the Shephelah. They can be reached at trentdutton@gmail.com.

Image 1: The Tel Shimron team performing a surface survey in 2015.

Image 2: Flint tools (left, clockwise): Knife, microblade, scythe blades, scraper, axe. Basalt tools (right, clockwise): Grinding bowl, tri-footed grinding bowl, hammer stone (from Ashkelon).

Image 3: Shimron was positioned at the junction of many trade routes.