by Trent and Rebekah Dutton

Synopsis: Using several relevant examples, Trent and Rebekah show that tablets from the ancient world can help us better understand actions and decisions in the biblical narrative.

Christians occasionally find themselves staring at a passage, wondering, "Why would he do that?" That's a perfectly acceptable question for 21st-century Westerners, and the sort of question that can be illuminated by the ancient texts that archaeology reveals. Two examples are Aaron's statement in Exodus 32:24 and Joshua's request in Joshua 10:12-13.

Aaron's defense in Exodus 32:24 has struck many a Bible class as nonsensical: "I cast [the gold] into the fire and this calf came forth."

In the ancient world, however, Aaron's statement may have been expected. Numerous tablets from 2000-600 BC throughout Mesopotamia describe a two-day ceremony for debuting new idols. They detail the artisans' oaths: "(I swear) I did not make (the statue)…" before their hands are symbolically "cut off."

Following mass sacrifices and celebration, like Exodus 32:6, the artisans swore that gods were indeed responsible, and the statue was "born." Other tablets explain: idols were made in a "birthing hut" on the birthing bed of Belet-ili (Mother Goddess)—the artisans simply functioned as midwives.1 We, like they, understand they made these objects, but we have no reason to doubt they sincerely believed the gods acted through them, like Bezalel, Aholiab, and the craftsmen of Exodus 31:1-6.

The significance of these tablets on Aaron's statement is three-fold. First, their geographic and temporal spread attest to a ritual that was almost certainly common knowledge. Secondly, Aaron, the artisan, denied making a god. Finally, even the calf was "birthed" when nuancing the translation of Exodus 32:24, "…I cast [the gold] into the fire, and this calf was born."2

Thus, was Aaron using a sophisticated evasion by referencing the artisan's oath, as though trying to convince Moses of the propriety of his actions? Or, by appearing to follow the culturally correct ritual for giving Yahweh an earthly avatar, did he believe the calf was born through divine means—demonstrating Israel's egregious misunderstanding of the God not made with hands? Regardless of the motive for his sin, Deuteronomy 9:20 tells us that Aaron only escaped God's wrath through Moses's intercession.

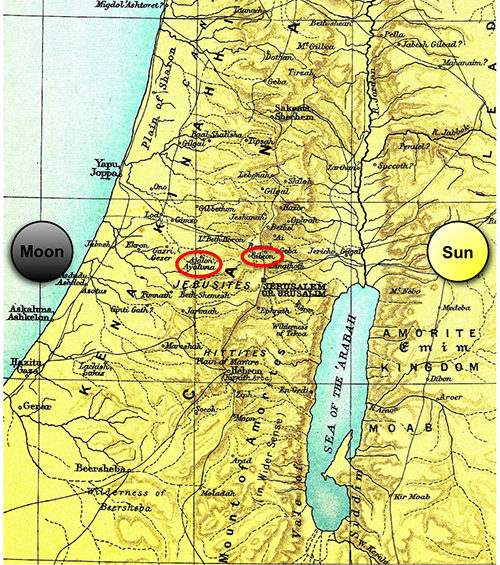

In Joshua 10:12, Joshua made a request that is sometimes called "The Longest Day." Yet, if Joshua simply wanted to extend daylight, why would he reference the moon and specify Gibeon and Aijalon? The sun, then, was in the east (Gibeon) and the moon in the west (Aijalon Valley)—apparently indicating that this prayer was made in the morning, before the events of the day.

Like artisan oaths, another series of tablets is just as far-flung geographically and temporally: celestial omens. Diviners throughout the Fertile Crescent were employed by kings and armies to interpret the gods' will through omens. Particularly noteworthy were lunar omens, since the Near East generally measured months by phases of the moon. Normal months were 30 "full" days, meaning the sun and moon stayed in their prescribed locations in "the midst of the sky," and the new moon appeared on the 30th day. The luck of kingdoms was inextricably linked to the first day of the full moon, which should land on the 14th day, "standing" or "waiting" until the sun rose, as in the omen: "When the moon and sun are seen with one another on the fourteenth day…the gods intend Akkad for happiness."

However, if they appear on the 12th, 13th, 15th, or 16th day, military defeat is at hand, as one tablet states: "When the Moon and Sun are seen with one another on the fifteenth day, a powerful enemy will raise his weapons against the land. The enemy will destroy the gate of my city."

If the sun and moon were on the east and west horizons in Joshua 10:12, then it was near the middle of the month, and the Amorites would be gazing skyward at dawn. It is reasonable to consider that Joshua, while perhaps wanting more daylight, may have also wanted a psychological blow—that the sun and moon hang in the sky on an inauspicious day, the omen of calamity. This interpretation of Joshua 10:10-14 is bolstered by both Habakkuk 3:11 and a tablet describing divine wrath: "The sun lay at the horizon, the moon stopped still in the midst of the sky…an evil storm..." God declared judgment in a way the Amorites recognized, leading to the confusion that routed their army.

Considering the culture and Joshua's terminology echoing celestial omens, a more refined translation may read: "So the sun waited and the moon stood, before the nation took vengeance on its enemies. Is it not written in the book of Jasher, 'The sun stood in the midst of the sky and did not hurry to set as on a day of full length?'"3

The inspired writers do not reveal the motives behind Aaron and Joshua's statements, and so any conclusions must only be possibilities. However, archaeology provides texts that help us understand that these events are neither laughable nor inexplicable.

Archaeology instead gives us an opportunity to view God's narrative through the lens of its ancient context, revealing a God and a people who understood the signs of their times (as in the case of Joshua), yet occasionally gave voice to idolatrous concepts (as in the case of Aaron).

1 These tablets use the Akkadian verb waladu, "to give birth or be born," which is a cognate of Hebrew yalad.

2 Hebrew yatsa is used numerous times to indicate birthing, including inanimate sea and ice (Job 38:8, 29), as well as being used synonymously with yalad in Deuteronomy 28:57.

3 See Walton, 190 for further explanation of this translation.

Cranz, I. "Ritual Contexts and Required Situations," in Atonement and Purification: Priestly and Assyro-Babylonian Perspectives on Sin and Its Consequences (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2017), 33-50.

Thompson, R. "When the Moon and Sun Are Seen with One Another," in Reports of the Magicians and Astrologers of Nineveh and Babylon (London: Luzac, 1900), lvi-lxii.

Walker, C. and Dick, M. "The Induction of the Cult Image in Ancient Mesopotamia: The Mesopotamian mīš pî Ritual," in Born in Heaven, Made on Earth: The Making of the Cult Image in the Ancient Near East, ed. M. Dick (Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 1999), 55-122.

Walton, J. "Joshua 10:12-15 and Mesopotamian Celestial Omen Texts." Faith, Tradition, and History: Old Testament Historiography in Its Near Eastern Context, ed. R. Millard, J. Hoffmeier, and D. Baker (Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 1994), 181-190.

Author Bio: Trent and Rebekah both hold Master's degrees in Biblical Archaeology from Wheaton College in the Chicago, IL area. They have participated in four full excavation seasons with the Leon Levy Expedition to Ashkelon, Israel, and two seasons at Tel Shimron in the Jezreel Valley. They can be reached at trentdutton@gmail.com.

Image 1: Tablet A.418 describes the “birth” of an idol, including a diagram in the lower right of how the birthing bed and images were to be arranged. Source: Istanbul Archaeology Museum.

Image 2: Map illustrating the locations of the sun and moon in Joshua 10.

Image 2: This planisphere, K.8538, demonstrates the precision with which astrologers tracked the celestial bodies. Source: British Museum.