by Steve Wolfgang

Synopsis: The theme section of the January issue of Truth Magazine offers several reviews and personal reflections on the 2017 Exploring Current Issues Conference (ECIC). This is a private Bible study hosted by Jim Deason that has been conducted in Cullman, AL since 2011. This year's study focused upon the similarities and differences between institutional and non-institutional churches of Christ.

If you've ever heard about "orphan-hating antis," or wondered who they are, this may help.

1. Who they are. Some mischaracterize them, whether ignorantly or maliciously (per Vergilius Ferm's Encyclopedia of Religion comment on "Campbellites"). They are not the same as those who oppose Bible classes, women teachers, or other issues which some people lump together in an effort to prejudice the uninformed.

2. They are indeed "anti" (opposed to) some things. It is fair to note that nearly everyone is anti-something: anti-poverty, anti-abortion, anti-Catholic, anti-secular humanist, anti-Calvinist, anti-false doctrine, etc. Not all who oppose one thing will unite to oppose other issues. The deck might need to be re-shuffled to correctly locate someone on any of these disputes. Some people have become known for being primarily anti-Anti.

3. What they oppose: churches becoming funding sources for human businesses. Leaders of the "non-institutional" (sometimes labeled "NI") approach insisted that it is not the task of churches to oversee "homes," schools, farms, etc., operated by orphanages "under the oversight of elders," or for churches to contribute to human institutions or business enterprises. Instead, they urged Christians to be as supportive and active as possible in caring for orphans and disadvantaged children by opening their own homes to them, by facilitating foster care or in-home care situations, or, if necessary, purchasing appropriate institutional care on a fee-for-service basis.

4. They don't really hate orphans. They actually care for them—and not just in an intellectualized sense of "caring." They take them into their homes as foster children – adopt them, in many cases. During the height of the division of churches in the 1950s over the best way to care for orphaned children, it became known that at Florida College (tarred by many as an "anti-orphan school"), the twenty-five families of the college faculty had taken into their homes at least seventeen children who were not the biological offspring of those families. Also, ten such children were being cared for by the eight families of the small editorial staff of the Gospel Guardian (labeled "anti-orphan" because of its opposition to the imposition of church-supported orphanages as the singular way mandated for churches to care for orphans). In 1965, a survey of merely sixty (of more than 2000) non-institutional churches revealed that more than 450 orphans were being cared for and adopted by "antis"—arguably more than the entire population of all the institutional orphanages operated by those who slurred them with the label "anti-orphan." More recently, the individually-supported group known as "Sacred Selections" has legally facilitated the adoption of hundreds of orphans by members of churches which do not contribute to human institutions of any sort (nor does Sacred Selections accept funds from churches).

5. The division over how to scripturally (or best) care for orphans was not limited to "antis," or those opposed to warehousing orphans in institutions. Even those who thought institutional orphanages were the best way to go about it were sharply divided about organizations and methods. Between about 1958 and 1964, pro-orphanage advocates waged a hot and heavy discussion in the "brotherhood papers" and other venues (and came near to dividing again) over whether churches could support only the orphanages under the direct oversight of a church with elders, or whether church-supported orphanages existing as a distinct human institution (under a board of directors from many churches) was scriptural or not.

6. "Antis" understand that some institutional orphanages can do "good works." Not only "Church of Christ" orphanages, but Baptist, Methodist, and Catholic orphanages. Presbyterian. Islamic and Hindu, even. Secular state-run orphanages. The question the "antis" raised was, "Does the fact that some good may be done in an institution mean that churches may (or are obligated to) support such human institutions?"

7. They agree with the bulk of social-science research which indicates that warehousing children in an institutional orphanage is just about the worst way possible to care for (especially already-traumatized) children. For some, that worked well —but in many cases, it did not (even among siblings of those for whom institutional orphanages worked out seemingly alright). Historically, orphanages have been rife with abuse – verbal, emotional, physical, sexual, and every other sort of abuse imaginable.

8. The division over orphanages a half-century ago was serious. Some have attempted to trivialize it in hind-sight ("just a few cranks isolated in dying churches," etc.) Historian Bill Humble of Abilene Christian University knew better: "The most serious issue that churches of Christ have faced in this century is church cooperation and 'institutionalism.'…a substantial number of churches have come to oppose such cooperative programs of evangelism as the Herald of Truth and the homes for orphans and aged, as they are presently organized…This is the most serious division, numbers-wise, that churches of Christ have suffered" (Story of the Restoration, Firm Foundation, 1969, p.74; on the Herald of Truth and sponsoring church issues, see also Richard Hughes, Reviving the Ancient Faith, pp. 239-243, 250-253; David Edwin Harrell, Churches of Christ in the 20th Century, pp. 120-175).

9. The division over orphanages a half-century ago was seriously ugly. Emotions ran hot. Treasurers given ultimatums: either write a check to the orphanage, or surrender the checkbook and leave. Lawsuits. Division publicized on the front pages of metropolitan newspapers. Fertilizer bags waved from pulpits (as in, "You antis would rather spend the Lord's money to spread manure on the church lawn than to care for a starving orphan"). How could this happen among brothers?

10. The "antis" main concerns were about congregational autonomy and the right of individual conscience. Churches were pressured to "line up" or be labeled "orphan-haters." Congregations and individuals in them found it prudent to avoid the stigma by sending $10 or $25 to an orphanage. (Those are not arbitrary or artificially-low numbers: Calculations from the published financial reports of institutional orphanages in the 1950's showed that the average contribution from a church was the stupendous sum of seven cents per member per week). Over this, churches divided and fellowship with brothers was sundered. Other issues of concern were the use of church-supported orphanages as "authority" for church support of colleges and other human institutions, the growth of fellowship halls into family-life and entertainment centers, and other similar issues.

What can be learned from all this? Maybe one of the chief "take-aways" to learn from this sordid past is not to let anything like it happen ever again. Perhaps it can strengthen resolve not to allow loyalty to a favored institution to take precedence over love for the brethren – even brethren not "clear-eyed" enough to see things as we do. Did not Christ die for them also? How then can Christians allow any humanly-devised arrangement to take precedence over the unity for which Christ prayed (John 17)?

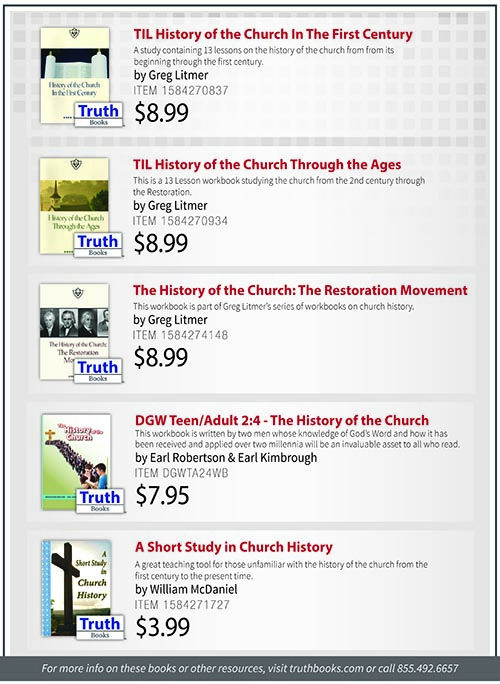

For further reading, see The Simple Pattern. Visit www.ceibooks.com or call (855) 492-6657. (Editor's note: For purchase information, click here and here.) Also available on Kindle and at Amazon.

Author Bio: Steve Wolfgang has preached the gospel since 1966 in local churches in Atlanta, Nashville, Louisville, and elsewhere, and in diverse places overseas, including Europe, Australia, Russia, and China. Since 2008 he has worked with the church at Downers Grove in suburban Chicago. Steve taught history at the University of Kentucky for nearly two decades, and is a co-editor of Psalms, Hymns, and Spiritual Songs. The church website is dgcoc.org. He can be reached at stevewolfgang@aol.com.