by Kyle Pope

Synopsis: People are sometimes confused by variations between English translations of Scripture. Such distinctions arise from different approaches to translation, changes in language that occur over time, and different textual foundations.

When I first began preaching, I was teaching a Bible class on the book of Romans. As we came to chapter eight someone in the class read the first few verses. After he finished, another member of the class raised his hand and said of the first verse, "My Bible doesn't say that." Most all translations begin the verse: "There is therefore now no condemnation to those who are in Christ Jesus"—but some translations end the verse with these words. Others continue, "…who do not walk according to the flesh, but according to the Spirit" (NKJV). Why would there be such a dramatic difference in the wording of these translations? What accounts for this difference and how can the student of Scripture evaluate which reading should be preferred?

Although one may believe that the Bible is God's word, preserved in its entirety through the ages, there are at least three reasons versions differ:

Imagine you were translating a letter for someone who spoke another language and you came to phrases such as "fits like a glove," "it's a piece of cake," or "let the cat out of the bag." You would have to decide whether to bring these expressions into the other language word-for-word or translate the sense of each phrase. If you kept it exactly as it is in English, you make what translators call a formal equivalence translation. If instead, you translated, "It's a piece of cake" to "It's very easy," you help the reader understand the basic idea, but you aren't doing a literal translation. This is what translators call a dynamic equivalence translation. Let's say you changed it even more to read, "It wasn't any trouble at all." In this case, you have moved even further away from the actual words while still translating the basic idea. This approach is called a paraphrase. There are challenges in each of these approaches. A translation that's too literal might leave someone looking for cats, gloves, and cake, but a translation that paraphrases too much won't let the reader see the words the author actually used. Different translations handle these challenges in different ways. Whenever a translator moves beyond exact wording, great caution must be exercised to avoid bias and error.

All languages change over time. Take, for example, the word silly. In its earliest form it referred to something blessed or worthy, but as time moved on it described things weak and vulnerable. Now we use it almost exclusively of things that are foolish. Some translations differ because of these kinds of changes. Newer translations may replace older expressions with modern wording so the older expression won't be misunderstood.

So let's think once again about how you would translate a letter. It's one thing if you had only one copy, but what if you had three—a hand-written version, a typed version, and a photocopy? Let's say that in the hand-written version some words were crossed out and other words were written above the line. Which words do you use to make your translation? Scholars call the process of determining the original text of a manuscript through the study of available copies textual criticism. That doesn't mean someone is "criticizing" the content of the text. Rather, it is the attempt to critically determine the best reading from the evidence. Some scholars argue that readings found in the oldest surviving texts should have priority. Others argue that readings represented in the most copies should be used. The choice a translator makes regarding what copies (or group of copies) to look to determines the textual basis that underlies a translation. This is one of the most significant causes of differences in translation. The final phases of our study we will consider factors that influence the textual basis used to translate Scripture.

The Holy Spirit has not preserved the original manuscripts of any biblical texts, but that should not lead us to doubt the accuracy and preservation of the biblical text. There are more than 5,600 known Greek manuscripts of the New Testament. When we add in early translations, the number grows to more than 20,000. Compared to the manuscript evidence for other ancient literature this is amazing! Many ancient texts have survived in only a handful of manuscripts. The works of Plato, for example, are preserved in only seven manuscripts. Only ten manuscripts of the works of Julius Caesar survive. Homer's Illiad is one of the most highly attested, with 643 copies, but in all of these cases the gap between the date of the earliest manuscript and the date it was originally written range from 500 to 1,400 years. There are fragments of New Testament manuscripts that date to the second and (possibly) late first centuries. No other ancient manuscript is attested by this kind of manuscript evidence.

Among these 5,600 manuscripts, there are many differences, but only a small percentage affect the meaning of the text. Most are spelling differences. Ancient people seldom followed standardized forms of spelling to the degree that we do. This is much like what can still be seen when comparing British vs. American spelling of English words. We understand that colour and color, or doughnut and donut are different ways of spelling the same words. Another difference involves multiple ways to say the same thing. In English, word order is quite limited. Let's say we wanted to write, "Joseph loved Mary." We could put it, "Mary, Joseph loved," but there are few (if any) other ways to express this same idea. Greek scholar Daniel B. Wallace has demonstrated hundreds of ways Greek could express exactly the same concept with slight variations in wording. Nothing changes in the meaning, but the form is different.

In some instances, words or phrases may be omitted or substituted. Some of this is likely due to the ancient process of copying texts that involved the reading of a text out loud while multiple scribes dictated what they heard. A busy scribe might substitute a similar word unintentionally. An example of this is seen in Matthew 15:6. Most texts speak of the "commandment of God," but some put it the "word of God." The meaning is essentially the same, but a variant exists nonetheless. In only a very few instances are there differences that affect meaning. In the example from Romans 8:1, mentioned in the beginning, a few manuscripts omit the last part of the verse while the majority of manuscripts include it.

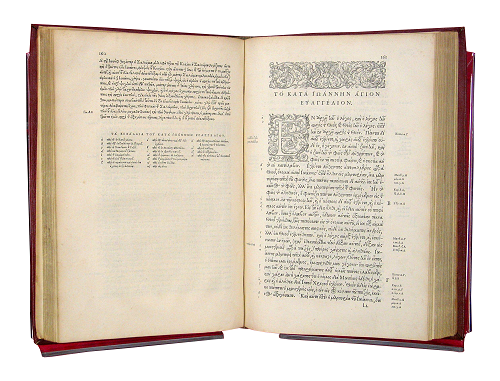

Translators can't consult 5,600 manuscripts, so how do they proceed? They must use editions men have compiled based upon their study of manuscript copies of the Scriptures. We noted in our last study the work of Desiderius Erasmus. In 1516, he published the first critical edition of the Greek New Testament. His work was followed by Robert Stephanus (the Latinized name of Robert Estienne). In 1550, Stephanus published a revision of Erasmus' text making use of more manuscripts. Stephanus' work came to be known as the "Text received by all" or Textus Receptus. Editions that came out after this were also called the Textus Receptus, including those of Elziver (1624) and Scrivner (1894). For nearly 400 years editions of the Textus Receptus served as the textual basis for all translations of the New Testament into English from the Greek.

The term Textus Receptus (or "Received Text") should not be misunderstood to mean that it was considered to be the form of the text received from God. Instead, this term was applied to the edition that gained general acceptance and reception among believers. It reflected the standard text used throughout the Greek-speaking world for centuries, known as the Byzantine text-type. It is clear that Erasmus and Stephanus only had limited access to Greek manuscripts, but the texts they published represent what is found in the majority of the manuscripts that have survived. In the nineteenth century, an important discovery would be made that led many scholars to reject the priority of the Textus Receptus and the Byzantine text-type. In our next study, we will explore this and other discoveries and consider its impact on the Bibles we now read.

Author-Bio: Kyle Pope preaches for the Olsen Park church of Christ in Amarillo, Texas. He has written several books published by Truth Publications including How We Got the Bible. The church website is olsenpark.com. He can be reached at kmpope@att.net.