by Leon Mauldin

Synopsis: The Amarna tablets help us to visualize life in the Canaanite city-states in the mid-second millennium BC.

Tell el-Amarna is an archaeological site situated along the Nile River in Egypt, about 170 miles southwest of Cairo. It is located on the eastern bank of the Nile, covering about six miles north to south. Abandoning the ancient capital of Thebes, Pharaoh Akhenaten (Amenhotep IV) made Amarna his new capital of Egypt in the fifth year of his reign (1352-1336 BC). (I understand that this period corresponds to the biblical era of Judges.) After his death, the city was abandoned and never rebuilt.

Peasants living in the area found a large hoard of clay tablets around 1887. The site was first excavated in 1891-1892 by Flinders Petrie, who was assisted by Howard Carter. By 1907, 358 tablets were in the collections of various museums.

Even though the language of Egypt was Hieroglyphics, the script employed in the tablets is the Babylonian language, Akkadian cuneiform, the diplomatic lingua franca of the day. As Charles Pfeiffer noted when the tablets were initially being read, cuneiform "seemed strangely out of place in Egypt" (Tell El Amarna and the Bible, 10). The tablets represent diplomatic correspondence between various vassal princes of the Egyptian empire and Pharaohs Amenhotep III and Akhenaten.

What is the biblical significance of the Tel-Amarna Tablets?

J. L. Kelley notes:

The Amarna Letters are particularly relevant for the field of biblical historical geography and archaeology. Biblical historical geographers correlate the ancient texts of the Near East with the study of the physical geography, toponymy, and geology of the land of the Bible and peripheral areas such as Egypt, Anatolia, and Mesopotamia. This type of research provides insight into both the texts and the geographical regions in question. Biblical historical geography relies on numerous texts from the ancient Near East, including the Bible and the vast corpus of extrabiblical epigraphic material from the Near East. The Amarna Letters contain a wealth of toponymic references that can be correlated with those of the biblical text. These place-names, along with those in the Bible, are particularly helpful in the identification of archaeological sites in Israel or Palestine (compare Aharoni, The Land of the Bible, 92–97; Rainey, The Sacred Bridge, 9–24). ("Amarna Letters," The Lexham Bible Dictionary.)

In addition to naming various biblical cities, the Amarna tablets also refer to the Hapiru. Some see a linguistic connection to the biblical Hebrews, though this is not certain. Fant and Reddish note,

The Habiru extended across several nations long before the Hebrews appeared in Israel and, therefore, cannot be equated with the Hebrews of the early chapters of the Bible. Nevertheless, when the descendants of Abraham, Isaac, and Joseph appeared in Palestine... they certainly would have been regarded as Habiru by the local inhabitants, and just as unwelcome (Lost Treasures of the Bible, 42).

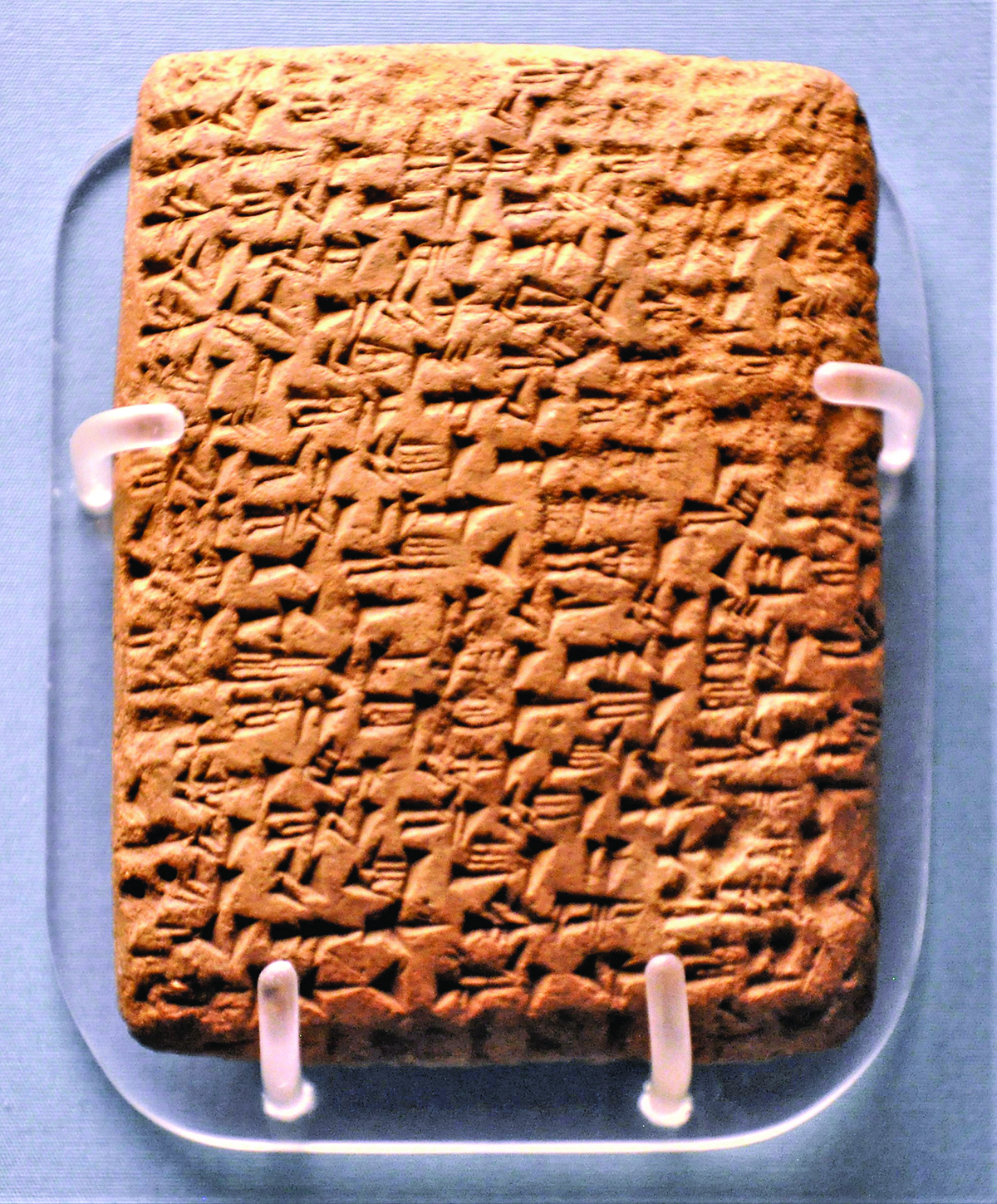

We here note two such tablets (referencing the Habiru) displayed in the British Museum. Here (E29832), the King of Gezer, identified as Yapahu, begs Pharaoh for help in defending his city against raids by the Habiru.

To the king, my Lord, my god, the Sun, the Sun [f]rom the sky: Message of Yapahu, the ruler of Gazru, your servant, the dirt at your feet, the groom of your horses. Truly I fall at the feet of the king, my lord, my god, and my Sun, the Sun from the sky, seven times and seven times, on the stomach and on the back. I have listened to the words of the messenger of the king, my lord, very carefully. Fully. May the king, my lord, the Sun from the sky, take thought for his land. Since the `Apiru [habiru] are stronger than we, may the king, my lord, [g]ive me his help, and may the king, my lord, get me away from the `Apiru lest the `Apiru destroy us.

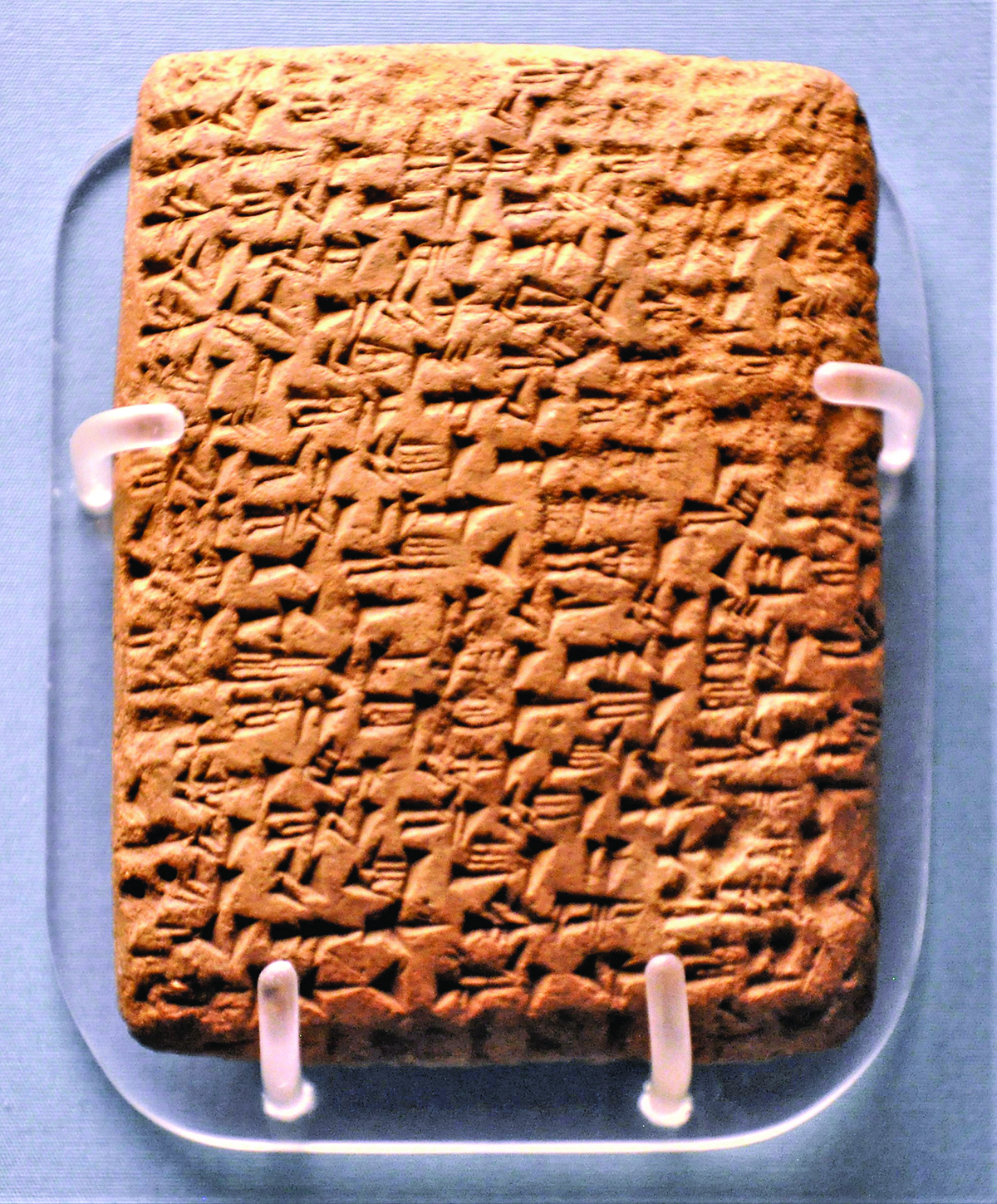

Another tablet (E29844) is from Labayu, ruler of Shechem. The accompanying placard reads:

From Labyu, Ruler of Shechem, who denies accusations of treachery and failure to comply with Pharaoh's orders. He justifies his capture of a certain town by quoting a proverb, "When an ant is struck, does it not fight back and bite the hand of the man that struck it?" It is significant that Labayu, the leader of the Hapiru, is seen as the ruler of Shechem, a city which lay in the heart of the hill country and which must have served as a power base for the Hapiru.

Though the Amarna tablets do not mention by name any biblical persons, they are of value in helping us to visualize life in the Canaanite city-states in the mid-second millennium BC.

Fant, Clyde E., and Mitchell G. Reddish. Lost Treasures of the Bible: Understanding the Bible through Archaeological Artifacts in World Museum. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2008.

Kelley, Justin L. "Amarna Letters." ed. John D. Barry et al. The Lexham Bible Dictionary. Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2016.

Pfeiffer, Charles F. Tell El Amarna and the Bible. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, 1963.

Author Bio: Leon has worked with the Hanceville church of Christ in Hanceville, AL for over thirty years. He and his wife, Linda, have three children and nine grandchildren. His websites are leonmauldin.blog and mauldinbiblelandtours.com. He can be reached at leon.mauldin@gmail.com. (Leon's next scheduled tour is for Greece/Turkey, Apr. 27-May 8,2020, In the Steps of Paul and John).

Image 1: This letter was sent from Yapahu, ruler of Gezer, to the Pharaoh of Egypt. British Museum, Exhibit #E29832.

Image 2: This letter was sent from Labayu, ruler of Shechem, to the Pharaoh of Egypt. British Museum, Exhibit #E29844.